By Business Insider Reporter

The East African Community (EAC) is confronting one of the most serious financial crises in its recent history, as an US$89.37 million funding shortfall threatens to paralyse its core institutions and derail momentum towards deeper regional integration.

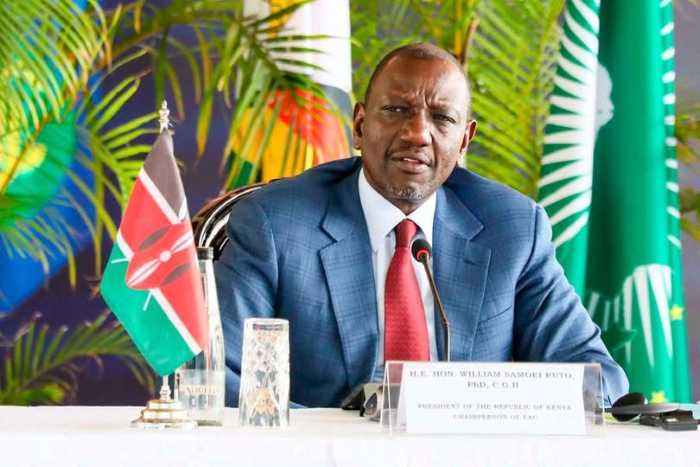

The EAC chairman, Kenya’s President William Ruto (pictured below) has convened an emergency summit of Heads of State in Arusha on March 7, marking the bloc’s first high-level meeting in over a year.

The summit is expected to address mounting arrears from Partner States and consider a new funding formula to prevent future operational breakdowns.

The anatomy of the shortfall

As of January 31, 2026, the EAC was owed US$89,372,865 in unpaid contributions. Under the current financing model, each of the eight Partner States is required to remit US$7 million annually to fund the Secretariat and affiliated institutions.

For the 2025/2026 financial year, only Kenya and Tanzania have paid their full assessed contributions.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo accounts for the largest share of arrears at US$27 million, followed by Burundi at US$22.7 million and South Sudan at US$21.8 million. Somalia owes US$10.5 million, Rwanda US$5.2 million and Uganda US$1.1 million.

While arrears have occurred before, the scale and concentration of non-payment now pose systemic risks.

Institutional paralysis

The financial squeeze has already paralysed key organs of the Community.

The East African Legislative Assembly (EALA), responsible for passing regional laws, has reportedly suspended sittings due to liquidity constraints.

Members have gone unpaid since November, undermining legislative oversight and raising concerns among creditors, including commercial lenders.

The East African Court of Justice (EACJ)- a cornerstone of the bloc’s legal framework – faces similar constraints, threatening dispute resolution mechanisms essential for investors and cross-border businesses.

Other specialised agencies are also affected. The Inter-University Council of East Africa is owed US$18.4 million, the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation US$2.1 million, and the Civil Aviation Safety and Security Oversight Agency in Kampala US$3.1 million.

What began as a fiscal delay has evolved into an operational crisis.

Why is the EAC facing a funding crunch?

The roots of the crisis are both structural and political.

First, the equal-contribution model does not reflect economic realities.

The EAC now includes economies of vastly different sizes and fiscal capacities, from Kenya – the bloc’s largest economy – to fragile and post-conflict states such as South Sudan and the DRC.

Expecting uniform annual contributions from countries facing domestic fiscal stress has proven increasingly unrealistic.

Second, several Partner States are grappling with debt burdens, currency pressures and reduced fiscal space. In such contexts, regional obligations often fall behind national priorities.

Third, the bloc has expanded rapidly. Since 2016, South Sudan, the DRC and Somalia have joined, stretching institutional resources without a commensurate revision of the funding model.

Finally, weak enforcement mechanisms mean there are limited consequences for non-payment beyond political embarrassment.

Risks to trade and investment

The timing of the crisis is particularly delicate.

The EAC has positioned itself as one of Africa’s most advanced integration projects, representing a market of more than 300 million people and serving as a bridge between the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

Operational paralysis could undermine investor confidence, especially in sectors dependent on regional regulatory harmonisation such as aviation, banking, telecommunications and cross-border infrastructure.

If the Court cannot function effectively or the Legislative Assembly cannot pass regulations, the legal certainty underpinning the common market weakens.

Beyond economics, the crisis carries symbolic weight. Regional integration depends on political trust and predictable cooperation. Persistent arrears signal fragility in collective commitment.

What should be done?

The Arusha summit presents an opportunity for reform rather than merely crisis management.

1. Adopt a revised contribution formula

A GDP-based or tiered financing model could better reflect economic capacity. Larger economies would contribute more, while smaller or fragile states would have proportional obligations.

2. Introduce automatic penalty mechanisms

Clear sanctions – such as temporary suspension of voting rights or access to certain regional programmes – could improve compliance.

3. Diversify revenue streams

The bloc could explore modest levies on selected cross-border transactions, customs revenues or digital services, reducing overreliance on direct state remittances.

4. Rationalise expenditure

Institutional efficiency reviews may identify cost-saving measures and overlapping mandates within EAC organs.

5. Strengthen political accountability

Ultimately, the crisis is political. Heads of State must reaffirm that integration is not optional but strategic — especially at a time of global trade fragmentation and shifting geopolitical alliances.

A test of political will

For President Ruto and his regional counterparts, the summit is more than a budgetary meeting; it is a test of whether East Africa’s political leadership can align financial discipline with economic ambition.

The EAC’s long-term vision – a monetary union and eventually a political federation – cannot advance on unstable fiscal foundations.

If leaders seize this moment to reform the funding architecture, the crisis could catalyse a more resilient and credible Community.

If not, recurring arrears may erode institutional effectiveness and stall one of Africa’s most promising regional projects. The coming weeks will reveal whether East Africa’s integration agenda is backed by sustainable financing — or remains vulnerable to the very national pressures it seeks to transcend.