By Business Insider Reporter and Agencies

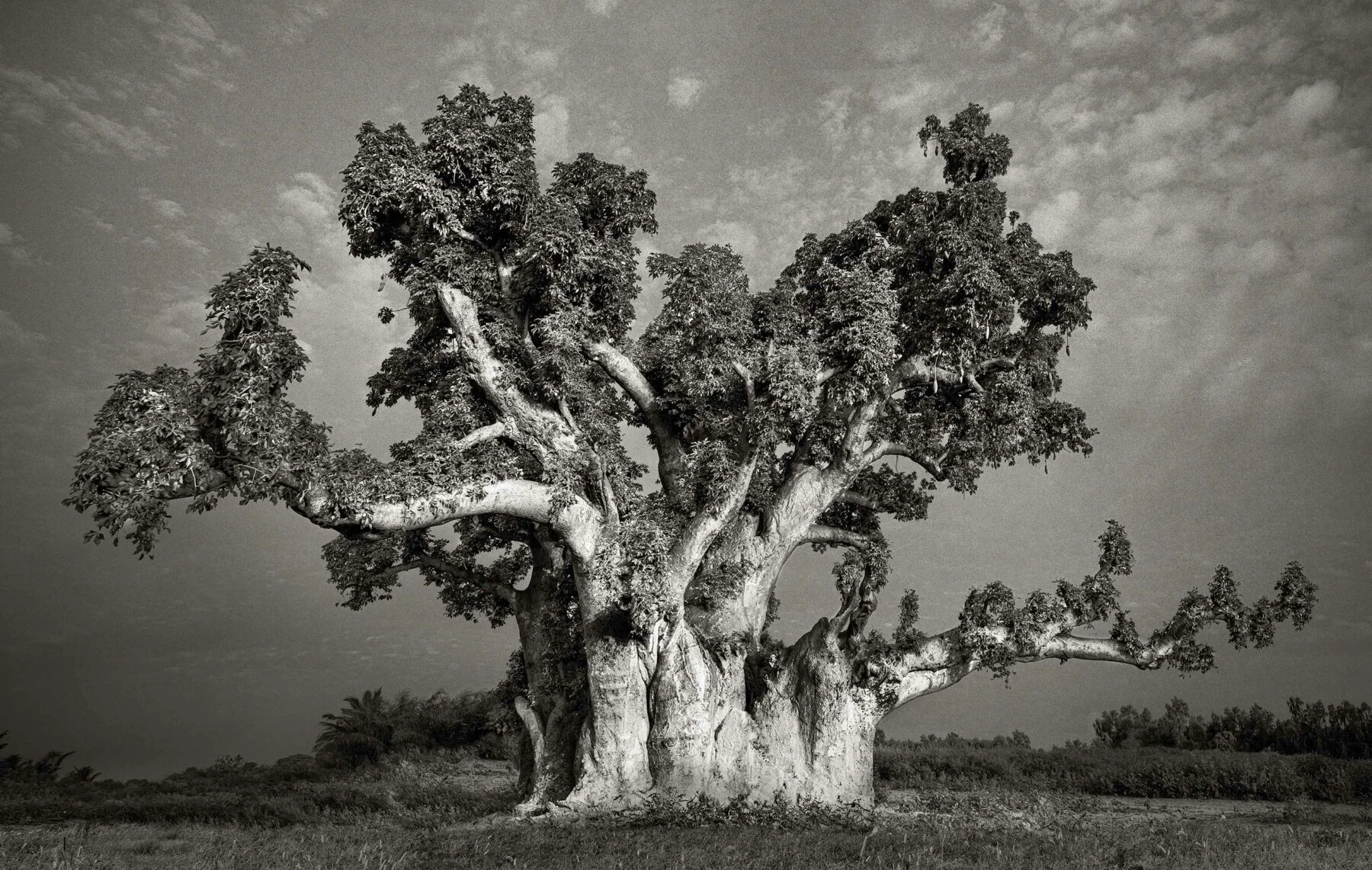

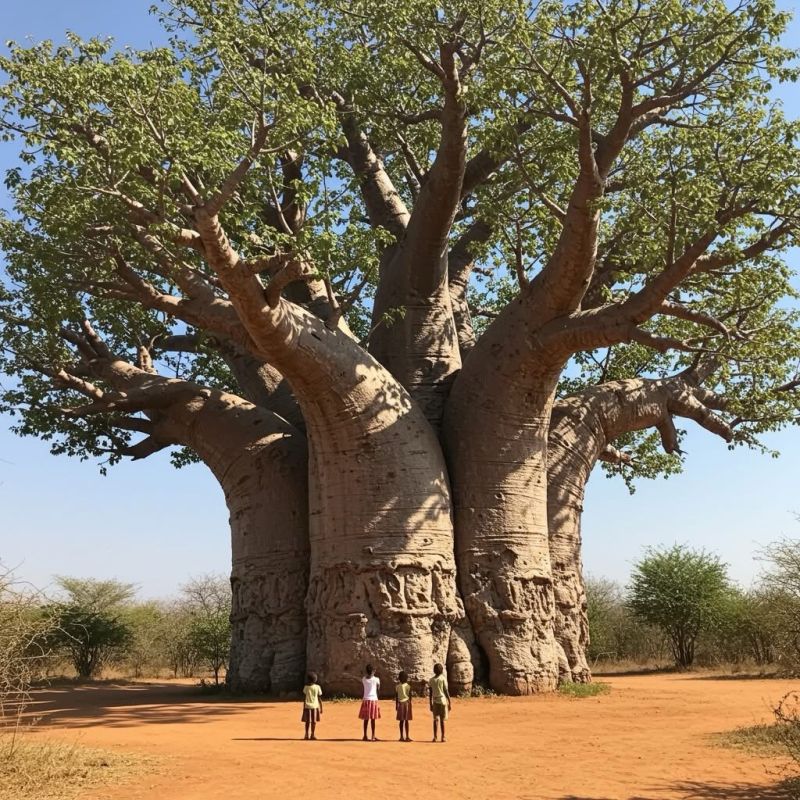

As Tanzania strengthens its global reputation for iconic wildlife and landscapes, one natural treasure often overlooked is the ancient baobab tree. These towering giants – known locally as mibuyu – define the savannahs of central and southern Tanzania, providing food, medicine, income and shelter for people and wildlife alike.

But new research from African ecologist, Dr. Sarah Venter, highlights just how fragile these giants are and why their survival depends on tiny nocturnal partners: bats and moths.

Baobabs, sometimes called “upside-down trees”, are among the continent’s most distinctive species. Of the eight baobab species worldwide, only Adansonia digitata grows across mainland Africa, including in Tanzania’s Mikumi, Ruaha, Manyara, Dodoma, Kondoa and Southern Highlands regions. For centuries, Tanzanians have harvested the fruit for juice, porridge and cosmetics, while communities use the bark for rope and the hollow trunks for water storage and shelter.

Yet the tree’s future hinges on a delicate ecological dance that happens only at night.

Baobabs bloom after sunset, producing huge white flowers filled with sweet nectar that attracts fruit bats and moths. As these animals feed, the flowers coat them in pollen, which they carry to the next blossom – a process essential for fruit and seed production. Without pollination, baobabs cannot reproduce. No fruit means no seeds, and over time, no new trees to replace the centuries-old giants.

Dr Venter’s team studied 284 baobab trees in Ghana, Kenya, South Africa, Namibia and Botswana, observing 205 hours of nocturnal activity. Their findings reveal that although African baobabs belong to the same species, the flowers have evolved differently depending on whether bats or moths dominate in the region.

In West Africa, the large straw-coloured fruit bat is the primary pollinator, prompting trees to develop long-stalked, nectar-rich flowers suited to big bats feeding upside-down. In East Africa – including large parts of northern Tanzania – the smaller Egyptian fruit bat takes the lead.

These bats crash-land directly onto flowers, so baobabs here have evolved smaller, sturdier blossoms with modest nectar but enough to keep bats returning through the night.

Further south, where baobabs receive no visits from bats at all, moths take over. Southern African trees have drooping petals, wide stigmas and sweeter scents designed to guide moths into perfect pollination position.

These adaptations took thousands of years to form, but they also mean baobabs are entirely dependent on their pollinators. If bat or moth populations decline due to habitat loss or climate change, baobab regeneration will falter – a serious concern for Tanzania, where the tree underpins rural economies, traditional medicine and cultural identity.

For conservationists, the message is clear: protecting pollinators is critical to protecting baobabs. Restoration projects must also match seeds and seedlings with the pollinator conditions of each region; a baobab adapted to bats may fail where only moths remain. In the end, Africa’s “tree of life” owes its future to some of nature’s smallest night-time visitors. Safeguarding them ensures that Tanzania’s baobab landscapes – and the communities rooted in their shade – endure for generations to come.