By Peter Nyanje

As the world marks the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), a new warning from United Nations leaders underscores a challenge that remains highly relevant to Tanzania’s long-term development ambitions: more than 4.5 million girls globally are at risk of undergoing FGM in 2026 alone – many of them under the age of five.

While Tanzania has made measurable progress in reducing the practice over the past two decades, FGM persists in several regions, posing not only a human rights challenge but also a significant economic and public health burden.

According to the UN, more than 230 million women and girls worldwide are living with the lifelong consequences of FGM, with global treatment costs estimated at US$1.4 billion annually. For countries like Tanzania – where public health systems are already under pressure – those costs translate into lost productivity, higher healthcare spending and reduced educational outcomes.

Tanzania’s progress – and persistent gaps

Tanzania criminalised female genital mutilation in 1998 under the Sexual Offences Special Provisions Act, popularly known in short as Sospa.

Since then, national prevalence has declined significantly, particularly among younger age groups, reflecting the impact of legal reforms, community engagement and education.

However, FGM remains entrenched in some communities, particularly in parts of Manyara, Arusha, Dodoma, Mara and Singida regions, where cultural norms and cross-border practices continue to undermine enforcement efforts.

Development experts note that the uneven persistence of FGM mirrors broader inequalities – rural versus urban access to education, income disparities and limited reach of health and child protection services.

“FGM is not just a cultural issue; it is a development issue,” one regional public health specialist told Business Insider Tanzania. “It affects girls’ education, women’s participation in the workforce, and long-term healthcare costs.”

The economic case for elimination

The UN joint statement – issued by the heads of UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women, WHO, UNESCO and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights – makes a compelling economic argument: every dollar invested in ending FGM generates a tenfold return.

An estimated US$2.8 billion investment globally could prevent 20 million cases and yield US$28 billion in economic returns through reduced healthcare costs, higher productivity and improved human capital.

For Tanzania, which has prioritised human capital development under its Vision 2050 and the Sixth Phase Government’s reform agenda, the implications are clear. Ending harmful practices such as FGM directly supports national goals on education, health, gender equality and labour force participation.

Girls who avoid FGM are more likely to stay in school, delay early marriage and childbirth, and enter productive employment – outcomes closely linked to higher GDP growth and lower poverty rates.

What works – and what is at risk

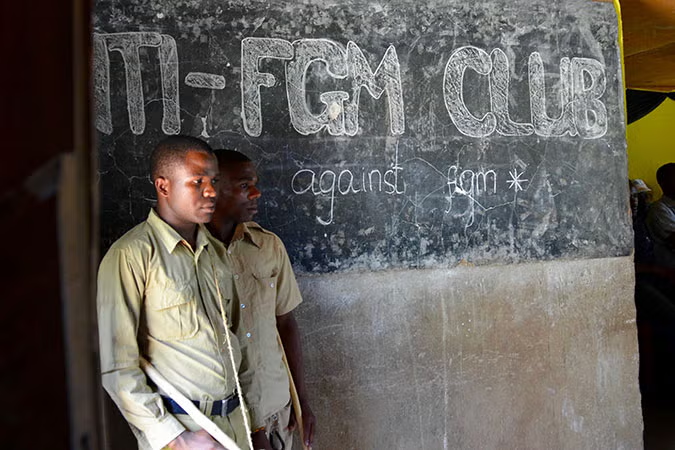

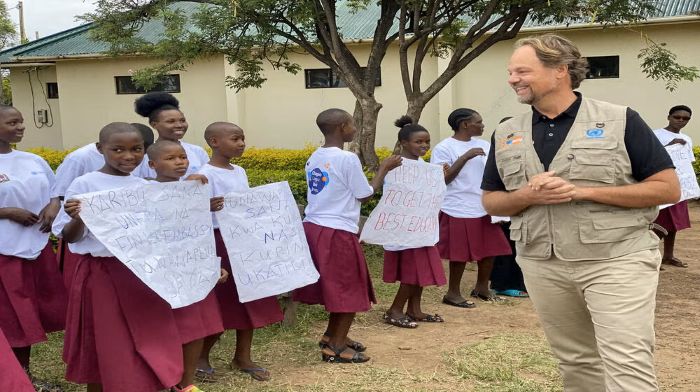

UN agencies point to evidence-based interventions that have driven progress across Africa, many of which have been applied in Tanzania with success: community-led education, engagement of religious and traditional leaders, involvement of health workers, and targeted use of mass and social media.

Grassroots organisations and youth networks have been particularly effective in shifting attitudes, with nearly two-thirds of people in FGM-practising countries now expressing support for ending the practice.

Yet those gains are increasingly fragile.

“As we approach 2030, the progress achieved over decades is at risk,” the UN leaders warned, citing declining global investment in health, education and child protection programmes.

For Tanzania, this warning comes at a sensitive moment. While donor-funded initiatives have historically supported anti-FGM programmes, funding volatility – combined with competing fiscal pressures – threatens the sustainability of community outreach, survivor support services and enforcement mechanisms.

There is also growing concern over attempts to legitimise FGM under the guise of “medicalisation”, where the practice is carried out by health workers. The UN agencies stress that FGM remains a human rights violation regardless of who performs it.

Beyond morality: a strategic investment

Tanzania’s experience shows that legal prohibition alone is not enough. Sustained financing, local ownership and integration into broader development strategies are essential.

As the government seeks to mobilise private capital, expand social infrastructure and strengthen human capital, experts argue that eliminating FGM should be viewed not only as a moral obligation, but as a strategic economic investment.

“Countries that fail to protect girls’ health and education ultimately pay the price in lower productivity and higher social costs,” said a senior development economist based in Dar es Salaam.

With just five years left to meet the Sustainable Development Goal target of ending FGM by 2030, the choice facing Tanzania – and its partners – is stark: scale up investment now, or risk reversing hard-won gains and placing another generation of girls at risk. The UN’s message is unequivocal. Ending FGM is achievable. It is affordable. And for Tanzania’s future workforce and economy, it is indispensable.